I agree with most of what The Post's editorial board wrote in the endorsement. I do, however, take issue with the implication present in this statement:

"Mr. Obama's greatest deviation from current policy is also our biggest worry: his insistence on withdrawing U.S. combat troops from Iraq on a fixed timeline. Thanks to the surge that Mr. Obama opposed, it may be feasible to withdraw many troops during his first two years in office."I know the economy is the issue now, but we are still at war. The idea that the "surge" (called an "escalation" when it was done in Vietnam) is an unqualified success should be critically examined, because what we conclude goes to the heart of the all-important question of what to do next. The election on November 4th is the most important in a generation or more, in part because American voters are about to determine the future of this war. Will we continue the occupation indefinitely, as John McCain would have it, or begin to withdraw as soon as is practical, as Barack Obama proposes?

The Washington Post, most other media and seemingly every member of Congress are now in lockstep with currently popular view that the "surge worked." Some even suggest that only a naive fool, coward or terrorist appeaser (a 21st century Neville Chamberlain) would have opposed such an obvious course of action.

Really? Why then—a year after the surge began (and six years into the war)—have we not even begun to pack to come home? Or even gotten back to pre-surge troop levels?

Because, you might say, the stated goal was to foster Iraqi "political reconciliation," creating breathing room for Iraqi leaders to get their fledgling democracy off the ground.

Great. So that should be well underway now, right?

Call me a skeptic.

The assertion that the surge was a success assumes that (1) the increased numbers of American troops and the clear-and-hold tactics that they employed were the primary factors in the reduction in violence, (2) the relative calm is sustainable when we eventually and inevitably withdraw from most of those areas, and (3) it will necessarily result in a stable, Western-oriented democracy in a time frame—and at a cost in "blood and treasure"—that will be acceptable to the American people.

It seems there's a lot of "assuming" going on. Again.

I sure hope those pan out better than the assumptions made at the beginning of the war.

You remember those, don't you? We were going to be greeted as liberators; would find weapons of mass destruction; Al-Qaeda was in Iraq (before we were); and the war would cost just $50 to $60 billion. (The White House economist who projected $100 to $200 billion was fired, by the way, for his wildly excessive estimate. Well, as of August 2008 the actual cost of the war is $550 billion. With the inclusion of long-term but very real costs such as rebuilding our military and providing lifelong medical care for a new generation of young war veterans, the actual cost will top $3 trillion, enough to fund Social Security for the next 50 years. And, of course, the cost of the shattered lives of ten thousands of servicemen, women and their families is incalculable, not to mention the cost to countless Iraqis.)

You remember those, don't you? We were going to be greeted as liberators; would find weapons of mass destruction; Al-Qaeda was in Iraq (before we were); and the war would cost just $50 to $60 billion. (The White House economist who projected $100 to $200 billion was fired, by the way, for his wildly excessive estimate. Well, as of August 2008 the actual cost of the war is $550 billion. With the inclusion of long-term but very real costs such as rebuilding our military and providing lifelong medical care for a new generation of young war veterans, the actual cost will top $3 trillion, enough to fund Social Security for the next 50 years. And, of course, the cost of the shattered lives of ten thousands of servicemen, women and their families is incalculable, not to mention the cost to countless Iraqis.)In reality, the buying of the cooperation of enemies with still-ongoing cash payments were as important to tamping down the violence as the well executed military operations were. And let's face it, their cooperation will evaporate like a puddle in the Anbar desert when the gravy train ends.

The violence may also be down because many Iraqis have just left the country or moved from their once-integrated Sunni/Shite neighborhoods to set up something akin to a self-imposed "apartheid" kind of separation. This can't possibly be helpful in a country that must quickly begin consensus-building and the practice of democratic compromise in order to stabilize their fragile government. There are discouragingly few signs of this happening.

An additional factor—one that Obama should argue more forcefully—is that Iraq's national and tribal leaders are keenly aware that a relatively quick exit may be implemented by the next American administration. Their positions are in jeopardy and the whole precarious house of cards will come tumbling down if they don't start compromising and learn to govern by consensus.

Rigidly adhering to a set timetable for withdrawal while ignoring changing "facts on the ground" would be certainly be foolish, but telegraphing a possible timetable for our withdrawal is not necessarily naive or wrong. He would never say it in public, of course, but even the threat of it is useful to General Petraeus. It's an important lever.

Obama need not be defensive about the position that he took on the surge, but he does need to better articulate what he opposed, why he opposed it, and to question without hesitation what the definition of "success" is without being afraid of being called a defeatist who doesn't want to "win."

Obama need not be defensive about the position that he took on the surge, but he does need to better articulate what he opposed, why he opposed it, and to question without hesitation what the definition of "success" is without being afraid of being called a defeatist who doesn't want to "win."Saying that the "surge worked" is like being down ten grand at a blackjack table, doubling down on a $300 bet, winning the hand and declaring you're in the black.

You're not, and you'll be risking much more just to get back to even.

Despite the enormous sacrifice, dedication and professionalism of American servicemen and women I do not believe that democracy will ever be imposed on the people of Iraq.

Not by us. Not by a long shot.

Maybe W should have paid a little more attention in History 101. John McCain, too.

While I concede that his "hundred years in Iraq" comment did not mean he would be fine with a hundred years of American military action, McCain has explicitly stated that he believes we can ultimately have a military presence in Iraq similar to our longstanding arrangements with Germany and South Korea.

That, my friends (as he might say), is not possible.

McCain's belief suggests an alarming lack of awareness of the basic current and historical realities of the region.

The fact is that the U.S.—an occupying, non-Islamic Western power—will never be accepted in Iraq.

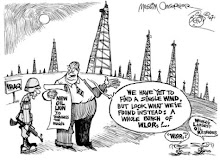

For a(nother) president to not grasp this would be a display of breathtakingly dangerous and consequential ignorance of the history of Mesopotamia. The nation of Iraq itself—in an area with a 7000-year history of bloodshed—is the 1920's creation of another occupying, non-Islamic Western power: the British. It was specifically designed to help with their exploitation of Middle Eastern oil reserves, despite the British proclamation that "Our armies do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators." (sound familiar?) The nation now known as Iraq was created in a deal in London from parts of the crumbled Ottoman Empire after World War I without the consent of the governed; the distinctly separate cultures of Kurdistan, the Shia in Basra and Sunnis of Baghdad.

For a(nother) president to not grasp this would be a display of breathtakingly dangerous and consequential ignorance of the history of Mesopotamia. The nation of Iraq itself—in an area with a 7000-year history of bloodshed—is the 1920's creation of another occupying, non-Islamic Western power: the British. It was specifically designed to help with their exploitation of Middle Eastern oil reserves, despite the British proclamation that "Our armies do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators." (sound familiar?) The nation now known as Iraq was created in a deal in London from parts of the crumbled Ottoman Empire after World War I without the consent of the governed; the distinctly separate cultures of Kurdistan, the Shia in Basra and Sunnis of Baghdad.The West's actions in the region have rarely (if ever) been motivated by a concern for the welfare of the people; nor is it today. The people know this, of course, and they have much longer memories than we do. To begin to appreciate the views of the Iraqi "street," U.S. policy must be viewed through the long lens of Mesopotamian time. When we say we are bringing them "democracy" many Iraqis understandably just see 150,000 occupying, non-Islamic Western soldiers in their country and hear about things like Abu Ghraib

Given the circumstances, how would you rate our chances at winning Iraqi "hearts and minds"?

It is a given that members of the U.S. military have performed their missions brilliantly and with a dedication that those of us who haven't served can never fully appreciate. I also know that the U.S. and British have done truly commendable humanitarian work throughout the current conflict.

We can't honor their service enough.

But we are not honoring them by perpetuating an unwinnable war that started with lies, incorrect assumptions, a lack of knowledge of culture and history, and a radical interventionist ideology to reshape the world in our image.

Giving your life for your country is never "dying for a mistake." When we

ask for their sacrifice, they (and their families) answer. Every time. There is nothing more honorable than that. There is no greater love.

ask for their sacrifice, they (and their families) answer. Every time. There is nothing more honorable than that. There is no greater love.If only the leaders that got us into this mess were half as honorable.

The surge worked, sort of. But the war has not. While it could have been prosecuted much better, it is not now, and never has been, a "winnable war." Not in the military sense.

John McCain knows the military, and he certainly knows sacrifice. We honor his. But when you only (think you) have a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.

A broader view of the world is needed at the top.

Vote for change.

Vote Obama.